Golf is a numbers game: swing speeds, ball speeds, spin rates, and launch angles. All this data should lead pro players down the path to righteousness, riches, and lower scores.

It will produce the ultimate power tool, a repeatable swing – or so the thinking goes.

But some think this is idiocy, complicating a simple game.

I grew up a fan of Lee Trevino, who played with a joyousness that was infective and effective. His homemade swing looked like an octopus assembling IKEA furniture, but it worked.

Only one number interested Merry Mex: the one on his scorecard.

I bristle when I see today’s grim-faced technocrats, tumbling back to Ben Hogan, the game’s mechanical man. It carries on with the robots produced at high-end golf academies and factory schools. These graduates play with assembly-line swings and have assembly-line personalities.

To me, this is anti-golf, played as it should not be played, without joy, or humanity. Trevino was a wisecracker, a stand-up comic with a +5 handicap.

The hulking, wonkish, Bryson DeChambeau, nicknamed “the mad scientist,” is the current face of the game – earnest to a tee.

He’s the ultimate number cruncher, who gobbles up digitized data like Pac-Man, then pulverizes it into a fine powder before sprinkling it on his golf swing.

And it seems to be working. He leans on his physics degree and has a workout regimen that would embarrass a Navy Seal. The result: he can mash a drive the distance of four football fields.

Maybe I’m too old, or easily irked by his look-at-me-I’m-great attitude, but it’s no surprise he wears a Hogan-style flat cap.

But I’m not a total Luddite. I understand numbers rule our game – especially the important ones issued in 2009. That’s when NAGA, the National Association of Golf Associations –representing club owners, manufacturers, retailers, and dozens of others – put aside their petty jealousies, travelled to Ottawa, and did battle with politicos over an issue that needed addressing: taxation. Would parliamentarians admit golf was a legitimate entertainment expense, and let players claim it as a tax write-off?

NAGA stakeholders had the game’s first Economic Impact Study tucked under their arms which showed through numbers how vital it was to the country. Golf generated $29.4 billion in gross production through direct, indirect and induced spending, and created 341,794 jobs. There were billions more in household income, property and other indirect taxes, and income taxes.

It was the first time the game was benchmarked, and a tax break would further enhance interest. In prepping for the meeting, a NAGA official said, “we want policy makers to take us seriously.”

They didn’t. The appetite for giving tax breaks to a game still viewed as a bastion of country-club privilege and played by the 1 percenters, would only inflame voters. Hell, Canadians were still struggling from an awful economy.

But NAGA was on to something, and called for new studies in ’14, and ’19. Laurence Applebaum, CEO of Golf Canada, and chair of We Are Golf, spoke for stakeholders when the last one was issued: “The multiple industry data sources from course operators, from the ’09, ’14, and ’19 studies, further reinforced the enormous financial, employment, charitable, tourism and positive environmental impact that the sport, and the business of golf are affecting across Canada.”

The key phrase was “positive environmental impact.” Two years ago, before COVID-19 and the world-wide ravages of climate change, eco-stewardship of golf was just a fanciful hope. By 2021, it was the ruling passion of the industry.

Is the golf industry doing enough to combat climate change? was the headline attached to a recent issue of GreenBiz, an online association that closely reports on this issue, offering a scientific take. It went so far as to suggest legislators “should help cities reinvest in retrofitting existing municipal and public golf courses.” This should include grants, new policies, or loans, to make municipal courses more accessible, inclusive, and able to incorporate renewable systems. Courses – private or public – can be living laboratories for regenerative and circular urban ecosystems.

Once golf decided to benchmark itself, it could use number power to do what other sectors did: peddle their influence. The first impact study also produced a cryptic aside: participation levels had fallen 10 per cent. No wonder. The game lacked diversity and was dominated by a dying-out demographic: the boomers, mostly old, white males. Women recoiled at this old boys’ network. Millennials were also uninterested. They only knew Arnold Palmer as a beverage that combined iced tea and lemonade and mixed well with alcohol to make a lovely summer cocktail.

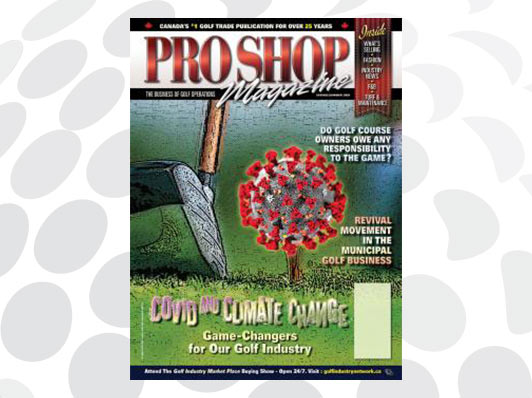

But in 2021, as our planet struggles, golf is on the ascendency, saved by not one, but two pandemics: COVID-19, and climate change.

The IPCC Special Report on Global Warming urges urban policy makers to accelerate ecosystem-based adaptation, and the use of natural systems to sequester carbon in their cities.

Why not golf as a tool to save us from ourselves?

What better way to help solve climate change than banking parkland, bringing back to life our eco-sensitive areas, and even acquiring more green lands for municipal golf courses? These can be used year-round by the golfers and public.

Golf, once a game that drew little interest from politicians, public health officials, or leaders in the green movement, has now drawn the attention of all three.

No, golf didn’t get those tax breaks in ’09, ’14, or ’19. But today, the game has gotten something more valuable: relevancy. It is now seen as the perfect antidote for the two greatest maladies infesting our planet: Covid and climate. It’s played outdoors and was already practicing social distancing. The mental and physical health benefits are clear to those still sheltering in place. The participation numbers have exploded since the pandemic struck. Using golf to help solve our climate change crisis is a story that has gone under-reported across the land.

The greenery of golf clubs, especially municipal ones, are not bastions of exclusion, or wastes of taxpayers’ money, but emerging economic engines that can drive down CO2 levels and act as an escape hatch for thousands of Canadians huddled in place by COVID-19.

This suggests to me that NAGA has to create a new impact study focusing on public health and the environment. The numbers will clearly show Ottawa how golf is a double-barrelled net positive for society.

My bet is that MPs will be much more receptive to NAGA stakeholders and offer active assistance to help them and Golf Canada fulfill their mandate to grow the game.

It’s unseemly to say this, but obviously true that the twin evils, COVID-19 and climate change, are now seen as a double shot of vaccine into the arm of a game that was once upon a time very sick – but getting healthier by the day.